Clearly, the debate about the inflation outlook remains intense with the difference in views as wide as ever. The "Big Picture" blog has just published a lengthy guest article laying down the foundations of the inflationary view (see here). I will first provide a brief summary and then comment on that view.

In short the authors "believe macroeconomic fundamentals imply longer-term US Treasury yields should be priced above 10%". The reason is that they expect inflation to rise to 10% for several years. They state: "money growth is inflation and generally rising prices are frequently derivative of that money growth...The Fed just doubled the monetary base over the past nine months...So, in monetary terms, we've witnessed a massive dose of inflation. The growth in the US monetary base is the permanent addition of money to the system."

This money the Fed created (via their asset purchases programes and lending facilities) went to the banking system in the form of reserves: "...money that everyone hopes the banking system will lend out to businesses, homeowners, consumers and investors at multiples of the Fed's mandated reserve requirements....and we can expect about USD8trillion in new credit chasing goods, services and assets. This new credit must help grow the economy in nominal terms because it will increase the nominal output of goods and services.....If we were somehow to attempt to annualize this paradigm shift, we would arrive at expected annual inflation that would easily exceed 10% for many years."

I have several problems with this reasoning. First, I do not regard a rise in the monetary base as being the same thing as inflation. Certainly, it can cause inflation (which I understand as an ongoing rise in the general price level) but there is not necessarily a 1:1 link. As I stated previously M*V=Y*P (i.e. the money times velocity of money equals output times price level) always holds because it is an identity. But that does not tell much. Unfortunately, there are various different forms of money (from 'high-powered' central bank money to broad credit aggregates) and additionally V is not a constant.

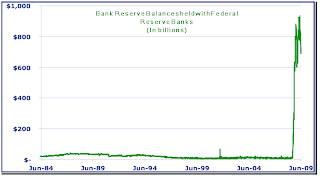

If the broad credit aggregates fall by more than narrow money aggregates rise, then V for narrow money aggregates is likely to fall (and it has been falling sharply over the past year). Additionally, just because the central bank creates more central-bank money, that does not mean that this will be hitting the economy. The authors themselves show this chart of banking reserves:

That is exactly where the additional central bank money went to (the sizes are almost identical). Banks hold the additional central bank money in the form of excess reserves, meaning that the credit creation process is not working and the additional money is not being used to chase goods and services. Only once the banks are able and willing to extend credit again (i.e. the credit crunch is over as the financial sector has brought its balance sheet in order again) and additionally corporates and households want to borrow again (as they have cleaned up their balance sheets) can these additional reserves help to increase broad credit aggregates. Furthermore, the authors state that the rise in the monetary base is a permanent increase and that the Fed will not drain this money. However, I do not see a convincing reason why they would not reduce - at least partially - their lending and asset purchase programs further down the road if the economic outlook brightens significantly and thereby reduce the monetary base (in fact, the 1930s US and the 1990s Japan history suggests that there has to be a considerable risk that this stimulus is bgeing reduced too early). Furthermore, as the chart the authors provide themselves shows, the US monetary base has been shrinking again over the past months (in line with the shrinking of the US Fed's balance sheet). Therefore, the jury is out on whether and how much of the increase in the monetary base will prove permanent.

As an aside, this article entitled 'When is rapid growth in a central bank's balance sheet not cause for concern?' makes an interesting point about bank reserve developments in New Zealand. In July 2006, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) changed the monetary policy operating system from a channel or corridor system to a floor system. "Under this floor system, the RBNZ stopped offering free collateralized daylight credit to banks for settlement purposes. In other words, they removed the distinction between daylight and overnight reserves. Also under this new system, reserves were remunerated at the official cash rate (OCR), the RBNZ's target interest rate." The new level of bank reserves increased by about 400times and moved to roughly NZD 8 billion (which corresponds to almost 25% of GDP). However, M1 was unmoved by this.

As the US Fed has started to pay for excess reserves, it should be expected that at least part of the rise in bank reserves is permanent and even once the ability of banks to extend credit is normalised and the demand for credit by corporates and households is rising as well, not all reserves will be used up.

So, in short broad based credit aggregates are falling by more than narrow-based monetary aggregates are rising. However, once broad-based credit aggregates are rising again (which can take a long time as it needs both, banks which are willing to lend and households/corporates which are willing to borrow), we should also expect narrow-based monetary aggregates to fall again. The ultimate inflationary pressure will be very limited and take a long time before it becomes evident.

For the time being, we still have too little money chasing too many goods resulting in disinflation or as in the case of Ireland in significantly negative inflation (or does anyone dare to say: deflation?):

No comments:

Post a Comment